The Fed and You (Part 2 – Maximum Employment)

This article is the second half of our two-part series on the Federal Reserve. You can find the first half here.

Last quarter, we described what the Fed is, how it operates, and what value it provides to the United States economy. We then focused on one of the Fed’s two mandates, inflation. This quarter, we focus on the other mandate, maximum employment. Maximum employment is defined as the highest level of employment or lowest level of unemployment that the economy can sustain while maintaining a stable inflation rate1.

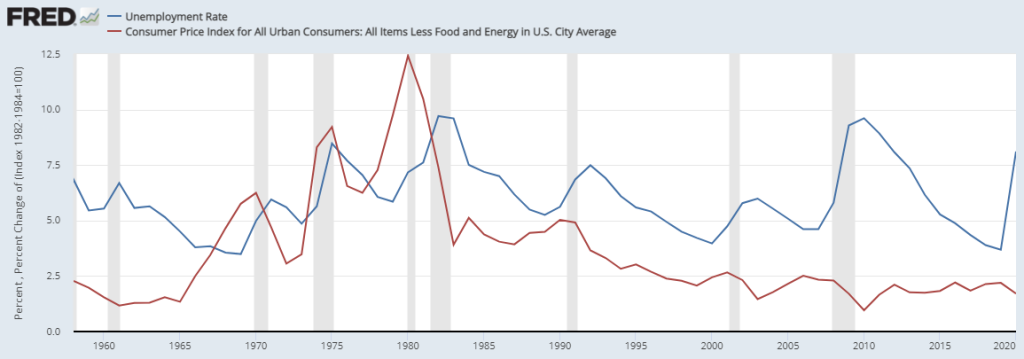

Note how there is no explicit maximum employment figure included in the definition. This is because there is no exact employment level that will always sustain the growth rate of the economy. Many factors go into how strong or weak the job market is, so the Fed needs to take as much data into account as they can when they are making their monetary decisions. Typically, however, unemployment levels will move in the opposite direction of inflation rates. This relationship is not perfect, but it’s the framework that the Fed has been using for decades.

1https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/what-economic-goals-does-federal-reserve-seek-to-achieve-through-monetary-policy.htm

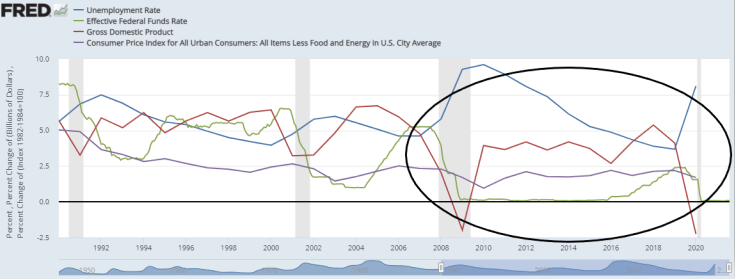

The Fed is always trying to do a balancing act between high growth, which typically brings along higher prices (inflation), and employment levels. The relationship between these variables was thought to be straight forward for many years, into the 2000s. However, the Great Recession in 2008-2009 helped to change this way of thinking. Hoping to spur growth, the Fed cut their effective funds rate to between 0%-0.25%. This helped the economy get back on its feet, bringing GDP back to a sustainable 3%-4% range and brought unemployment levels back down. However, instead of causing inflation to rise, it stayed low.

This begs the question – what is the optimum level of unemployment? Unfortunately, this question has no answer. We know that financial markets, along with employment levels, move in cycles. This inherently means that the Fed cannot keep their monetary policies the same over time. Specifically with the job market, there will always be some level of unemployment. Some examples of this include workers will take a break from working for various reasons, they may need to undergo training to qualify for the jobs available, some workers will lose their job for performance reasons, and employers will change the amount of staff that they need due to things like technological advances. There will always be influxes of workers into the job market as well, with college graduates being an example2.

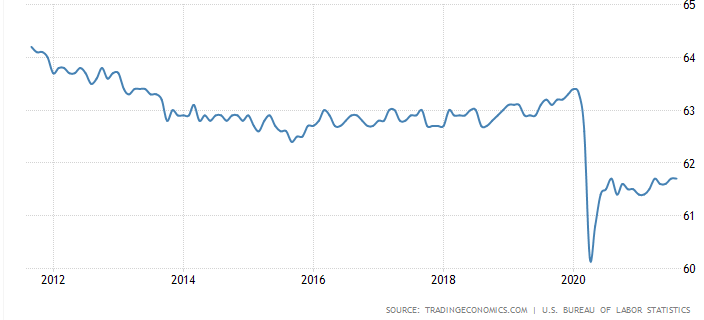

All of these examples are aggregated into something referred to as frictional unemployment. It is generally accepted that frictional unemployment is inherently present and will keep unemployment above 0%, but there is not a solid answer to what that level is. The pandemic has brought its own unique set of challenges for the Fed. Millions of jobs were lost in the spring and summer of 2020, as employers cut staff due to lack of demand and changing market conditions. The economy quickly bounced back late in 2020 and so far in 2021, but the job market is now at a strange place. While we are still 5.3 million jobs short of where we were prior to the pandemic, we have low unemployment levels, rising wages, and employers who are having trouble filling their payrolls. This is because the pool of people looking to work has shrunk. There are many reasons why workers have exited the work force, but some pandemic related examples are early retirements, safety concerns, and difficulties related to child care. This pool of workers is measured by the “participation rate.”

2https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/economy_14424.htm

The decline in the participation rate you see in 2020 represents millions of workers, and we are still far from recovering to the level seen prior to the pandemic. This presents a challenge to the Fed, as they try to balance rising inflation with a job market that looks strong on the surface given that the unemployment rate is low, but has yet to fully recover all the jobs lost.

In September, Chairman Jerome Powell said that they plan on tapering their asset purchases starting at the end of this year and could possibly end this process by the middle of next year. This was widely expected due to current inflation levels and is the first step the Federal Open Markets Committee will take in “normalizing” monetary policy – basically removing the extra liquidity it has injected into financial markets. The Committee has also indicated that they may start raising their benchmark rate next year. Ultimately, they are indicating that they are growing concerned with the current high level of inflation and are confident that these moves will not greatly affect the job market in a negative way.

The Federal Reserve, and its Federal Open Markets Committee that makes these monetary policy decisions, have a difficult task in balancing inflation and employment, which directly affects growth of the U.S. economy, and indirectly affects monetary policies in countries outside of the United States as well.